Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum at North Little Rock

Welcome to the blog for the Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum, home of the historic submarine USS Razorback (SS 394).

Saturday, December 19, 2009

A Naval Hero From Arkansas

Today is the birthday of Admiral Charles Maynard "Savvy" Cooke, Jr.

Admiral Cooke was born in Fort Smith on 19 December, 1886. He graduated from the University of Arkansas in only two years while also working full time on local road repair crews.

He entered the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD, where he graduated second in the Class of 1910, earning the nickname "Savvy". According to his classmates, the nickname reflected Midshipman Cooke's common sense and practicality as much as his academic billiance.

As was the tradition of the day, he was not immediately commissioned, but instead served on various ships, including the battleships USS Connecticut, USS Maine, and USS Alabama. During this time he met, courted, and married Helena Leslie Temple, the daughter of a prominent family from Philadelphia.

On 17 November, 1913, then Ensign Cooke reported to submarine school, then held in New York Harbor aboard USS Tonopah, an ironclad monitor, long since removed from front line service and pressed into duty as a floating classroom.

Picked for early promotion during his submarine training, Savvy Cooke first reported for duty as the Executive Officer of the submarine K-2. Less than a month later, he became Commanding Officer of USS E-2, after that's submarine's CO was severely injured in an accident. Seawater entered the battery well of E-2 sending deadly chlorine gas throughout the small submarine.

Just a few months after assuming command of E-2, then LT(jg) Cooke was in New York harbor, on the deck of his former school ship Tonopah, when he saw the wake of a passing boat swamp a small canoe. The two teen-aged boys in the canoe were swept overboard, into the frigid waters of the harbor. One boy was trapped under the overturned canoe. Without hesitation, Savvy lept into the water, risking his own life to save both boys.

Savvy's courage would be tested again on 16 January, 1916 when experimental batteries installed aboard E-2 exploded, killing four men outright and injuring ten, one of whom would later succumb to his injuries. At the time of the explosion, Savvy was aboard the nearby submarine tender USS Ozark (the former monitor USS Arkansas). He immediately rushed to his stricken submarine, and led a group of men inside to rescue his injured crewmen, despite the obvious dangers.

Savvy Cooke and his crew were completed absolved of blame in the accident. Despite this, he spent the next two years in shore duty assignments.

In December 1918, a newly promoted LCDR Cooke was assigned to the outfitting of USS R-2, a submarine then still being built. His mother christened R-2 and Savvy became her first CO when she was commissioned on 24 January, 1919.

He repeated the process for the larger submarine S-5. When S-5 sank on 01 September, 1920 while in transit from Boston to Baltimore, Savvy Cooke was able to lead his crew on a successful escape from the sunken submarine.

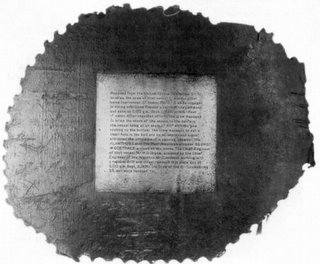

With her bow stuck in the mud, S-5's after ballast tanks were blown, bringing her stern just above the water. Even though the decks were nearly vertical, and they only had hand tools (their one electric drill failed after a short time), S-5's crew was able to cut a small triangular hole, six inches wide by eight inches tall through the 3/4" thick steel hull. The crew was able to attract the attention of a passing freighter, the steamer Alanthus. With the help of the crew from the Alanthus and another passing ship, the passenger steamer General George W. Goethals, the small hole was enlarged enough to allow every man from S-5's crew to escape.

The plate cut from S-5's hull is on display in the US Navy Museum in the Washington Navy Yard:

(From the book Under Pressure: The Final Voyage of Submarine S-Five by A.J. Hill)

The straight edge on the right side of the plate is one side of the hole cut by S-5's crew.

Following the S-5 disaster, Savvy Cooke's career continued to advance. He served in a succession of increasingly important assignments, both ashore and at sea, then was assigned as Commanding Officer of the battleship USS Pennsylvania in February, 1941. Captain Cooke had remarried following the tragic death of his first wife. Although his family had usually accompanied him, in 1941 Captain Cooke sent them to California because he believed war was coming.

"Savvy" Cooke was right.

Surviving the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Captain Cooke oversaw the repair of his ship, but was transferred to the Navy's Strategic Planning Division in Washington, DC when Pennsylvania was ready to return to battle. Quickly promoted to Rear Admiral, by 1945 he had been promoted again to Vice Admiral, was head of Strategic Planning for the entire Navy, and was the principal adviser to Admiral King, Chief of Naval Operations.

Savvy Cooke still saw his share of action. He was present at the Normandy Invasion and went ashore at noon on D-Day.

Although he almost certainly would have been an outstanding fleet commander during the war, it was believed that he performed a far more valuable service in his role in Strategic Planning. One of his contemporaries said that of all those unsung heroes who helped win WWII, Savvy Cooke's name "stands out at the top".

After the war, Admiral Cooke spent two years in China, trying unsuccessfully to bolster support for the Chinese Nationalists. He then served as Commander, Seventh Fleet, retiring in early May, 1948.

Admiral Charles M. Cooke, Jr died on 24 December 1970. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

(Sources: Under Pressure: The Final Voyage of Submarine S-Five by A.J. Hill and the US Naval Historical Center)

Thursday, December 17, 2009

In Memoriam - USS F-1 (SS-20) - Sunk 17 December 1917

On the morning of 17 December, 1917, USS F-1 (SS-20), along with her sister ships F-2 (SS-21) and F-2 (SS-22), got underway for an engineering test. The plan was to steam south from San Pedro to Point Loma, then return. The submarines, designed in the early 1900s and commissioned in 1912 could only make 10 knots on the surface. The round trip was scheduled to take about eight hours.

Since heavy fog is common off the California coast in winter, the plan for the engineering test included a contingency plan for the three submarines to turn to seaward if they ran into poor visibility.

F-1 was closest to the shore, with the other two submarines to her west.

About 1830, the three submarines encountered the expected thick fog. F-1 turned slightly west and sent a radio message to the other two submarines reporting her course change. Unfortunately, this message was not received by the other two boats. F-3 continued on her course south, and F-1 passed behind her, unseen.

At 1904, F-3 began turning to starboard with the plan of reversing course to the north to quickly exit the fog bank.

Eight minutes later, F-1's lights were spotted. The two submarines were on a collision course with a combined speed of nearly 20 knots.

Despite last minute maneuvers by both submarines, F-3 struck F-1 at nearly a right angle, near the bulkhead between the control room and the engine room.

The four men on F-1's makeshift bridge were thrown into the water. A fifth man manged to climb out of the control room, but he was the only one to get out of the doomed submarine.

Nineteen men perished in the accident.

In October, 1975, USNS De Steiguer (T-AGOR-12), an oceanographic research ship, located in 635 feet of water. The hull is laying on its starboard side, with the hole made by F-3 clearly visible.

Photographs courtesy of the U.S. Naval Historical Center.

In Memoriam - USS S-4 (SS-109) - Lost 17 December 1927

USS S-4 (SS-109) sank on 17 December 1927 after being accidentally rammed by the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Paulding during tests off the New England coast.

Originally commissioned in 1919, in 1920-21, S-4 made a historic voyage from New London, CT through the Panama Canal, to Pearl Harbor and on to Cavite, Philippines. At the time, it was the longest voyage ever undertaken by an American submarine. S-4 traveled as far as the coast of China during her tenure in the Far East.

In 1925, S-4 was reassigned to the West Coast and she returned to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, where she had been built, in early 1927 for dry docking, maintenance, and modernization.

Following the refit, S-4 put to sea for the normal series of post-dry docking tests, escorted by a US Coast Guard cutter, Paulding.

During these tests, tragedy struck.

After completing a submerged run at full speed, S-4 began to surface. The Coast Guard cutter was not equipped with sonar, and her crew misjudged their position in relation to the submerged submarine.

The Coast Guard Cutter's crew spotted the submarine's periscopes, but not in time to prevent the collision. S-4 was struck in her Battery Compartment, which was forward of the Control Room and Conning Tower. Part of the Coast Guard Cutter's bow broke off inside S-4.

The submarine's entire crew survived the initial accident. Men in the Battery Compartment tried in vain to stop the flooding, but had to quickly retreat to the Control Room, then to the Engine Room as flooding progressed. Six men were trapped in the Forward Torpedo Room, the remaining 28 men were trapped aft, in the Engine Room and Motor Room.

The submarine settled to the bottom in 110' of water.

By the time divers arrived on the scene, the men in the after compartments had already succumbed to the combination of cold, chlorine gas, and falling oxygen levels, but the six men in the forward torpedo room were still alive and were able to communicate with the divers on the outside by tapping on the hull.

Unfortunately, S-4 was not designed with a forward torpedo room escape trunk and by the time air lines and special fittings could be hooked up, the CO2 level had risen to 7%, far too high to support human life.

The failure to rescue S-4's crew raised a very public outcry and forced the Navy to being exploring means of both submarine escape and submarine rescue, ultimately leading to the development of the Momsen escape lung and the Momsen-McCann Diving Bell.

The successors of both of these devices are still in use today. American submarines now carry the SEIE, or Submarine Escape and Immersion Equipment, a full-body suit that allows escape from a submarine at 600', or almost six times deeper than S-4.

The Momsen-McCann Diving Bell has become a host of submarine rescue equipment, including the Submarine Rescue Chamber, as well as specialized, self-propelled rescue submarines.

While the loss of men aboard S-4 was tragic, they did not die in vain.

Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Naval Historical Center.

Thursday, December 10, 2009

In Memoriam - USS Sealion (SS-195) - Sunk 10 December 1941

The first American submarine to fall victim to a Japanese attack was USS Sealion (SS-195). The start of World War II found her, along with her sister ship, USS Seadragon (SS-194) in the final stages of an extensive overhaul at the Cavite Navy Yard, Philippines. The two submarines were moored side-by-side.

On the afternoon of 10 December, a group of 54 Japanese planes attacked the shipyard.

Only two Japanese bombs actually struck Sealion. The first exploded outside the conning tower. In addition to destroying a machine gun mount on Sealion, a fragment from this bomb pierced Seadragon's conning tower, killing one officer.

A second bomb struck Sealion aft, penetrating the pressure hull and entering the after engine room, where it exploded, killing four men.

Damage from the explosion and resulting flooding was extensive. All motor controls, reduction gears and main motors were destroyed. Sealion was completely immobilized.

Unfortunately, the Cavite Navy Yard was nearly completely destroyed by the same Japanese attack, and repairs were impossible. Nor was it practical to tow the submarine some 5,000 miles to Pearl Harbor, the nearest working repair facility.

All valuable gear such as gyroscopes, radios and sonar equipment was removed from the crippled submarine.

On Christmas Day, 1941, three depth charges were exploded inside Sealion's hull to prevent her from being used by the enemy.